-

Volume 81,

Issue 10,

2000

-

Volume 81,

Issue 10,

2000

Volume 81, Issue 10, 2000

- Insect

-

-

-

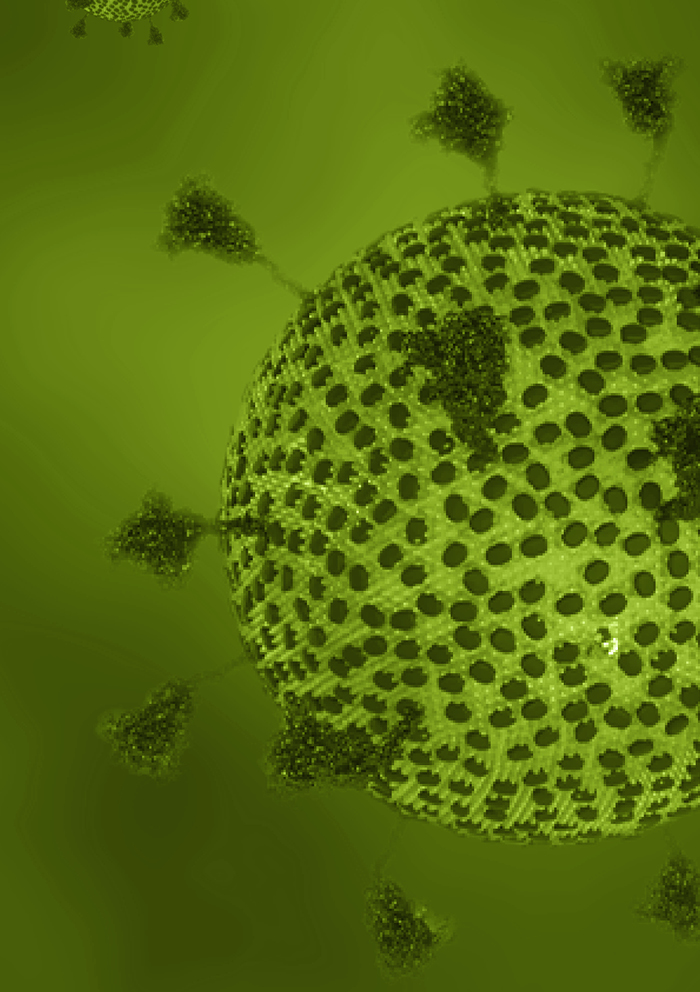

Three functionally diverged major structural proteins of white spot syndrome virus evolved by gene duplication

More LessWhite spot syndrome virus (WSSV) is an invertebrate virus causing considerable mortality in penaeid shrimp. The oval-to-bacilliform shaped virions, isolated from infected Penaeus monodon, contain four major proteins: VP28, VP26, VP24 and VP19 (28, 26, 24 and 19 kDa, respectively). VP26 and VP24 are associated with the nucleocapsid and the remaining two with the envelope. Forty-one N-terminal amino acids of VP24 were determined biochemically allowing the identification of its gene (vp24) in the WSSV genome. Computer-assisted analysis revealed a striking similarity between WSSV VP24, VP26 and VP28 at the amino acid and nucleotide sequence level. This strongly suggests that these structural protein genes may have evolved by gene duplication and subsequently diverged into proteins with different functions in the WSSV virion, i.e. envelope and nucleocapsid. None of these three structural WSSV proteins showed homology to proteins of other viruses including baculoviruses, underscoring the distinct taxonomic position of WSSV among invertebrate viruses.

-

-

-

-

Virus morphogenesis of Helicoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus in Helicoverpa zea serum-free suspension culture

More LessHelicoverpa armigera single nucleopolyhedrovirus (HaSNPV) replication in Helicoverpa zea serum-free suspension culture was studied in detail and the sequence of virus morphogenesis was determined by transmission electron microscopy. By 16 h post-infection (p.i.), virus replication was observed in the virogenic stroma by the appearance of nucleocapsids. Polyhedron formation was detected by 24 h p.i. and the polyhedron envelope (PE) was completely formed by 72 h p.i. PE morphogenesis of HaSNPV is significantly different compared to the extensively studied Autograph californica (Ac)MNPV. In AcMNPV-infected cells, fibrillar structures are found in both cytoplasm and nuclei, and the fibrillar structures in nuclei are in close association with maturing polyhedra during PE formation. Fibrillar structures that resemble the AcMNPV fibrillar structures were detected only in the cytoplasm of HaSNPV-infected cells and appeared to interact with calyx precursors there, but their role in PE formation is unclear. However, prominent calyx precursor structures of various shapes and sizes were observed in the nuclei of HaSNPV-infected cells as well, and they appeared to interact with polyhedra during PE formation. Both the calyx precursor structure and the cytoplasmic fibrillar structure were detected only after HaSNPV virion occlusion had started, indicating that they might have a role in formation of PE. Similar calyx precursor structures and cytoplasmic fibrillar structures were observed in both serum-supplemented and serum-free suspension cultures, as well as in HaSNPV-infected larval tissues, indicating that the structures observed are not cell culture artefacts.

-

-

-

Isolation of a Spodoptera exigua baculovirus recombinant with a 10·6 kbp genome deletion that retains biological activity

More LessWhen Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (SeMNPV) is grown in insect cell culture, defective viruses are generated. These viruses lack about 25 kbp of sequence information and are no longer infectious for insects. This makes the engineering of SeMNPV for improved insecticidal activity or as expression vectors difficult to achieve. Recombinants of Autographa californica MNPV have been generated in insects after lipofection with viral DNA and a transfer vector into the haemocoel. In the present study a novel procedure to isolate SeMNPV recombinants was adopted by alternate cloning between insect larvae and cultured cells. The S. exigua cell line Se301 was used to select the putative recombinants by following a green fluorescent protein marker inserted in the p10 locus of SeMNPV. Polyhedra from individual plaques were fed to larvae to select for biological activity. In this way an SeMNPV recombinant (SeXD1) was obtained with the speed of kill improved by about 25%. This recombinant lacked 10593 bp of sequence information, located between 13·7 and 21·6 map units of SeMNPV and including ecdysteroid UDP glucosyl transferase, gp37, chitinase and cathepsin genes, as well as several genes unique to SeMNPV. The result indicated, however, that these genes are dispensable for virus replication both in vitro and in vivo. A mutant with a similar deletion was identified by PCR in the parental wild-type SeMNPV isolate, suggesting that genotypes with differential biological activities exist in field isolates of baculoviruses. The generation of recombinants in vivo, combined with the alternate cloning between insects and insect cells, is likely to be applicable to many baculovirus species in order to obtain biologically active recombinants.

-

- Other Agents

-

-

-

Expression of unglycosylated mutated prion protein facilitates PrPSc formation in neuroblastoma cells infected with different prion strains

More LessPrion replication involves conversion of the normal, host-encoded prion protein PrPC, which is a sialoglycoprotein bound to the plasma membrane by a glycophosphatidylinositol anchor, into a pathogenic isoform, PrPSc. In earlier studies, tunicamycin prevented glycosylation of PrPC in scrapie-infected mouse neuroblastoma (ScN2a) cells but it was still expressed on the cell surface and converted into PrPSc; mutation of PrPC at glycosylation consensus sites (T182A, T198A) produced low steady-state levels of PrP that were insufficient to propagate prions in transgenic mice. By mutating asparagines to glutamines at the consensus sites, we obtained expression of unglycosylated, epitope-tagged MHM2PrP(N180Q,N196Q), which was converted into PrPSc in ScN2a cells. Cultures of uninfected neuroblastoma (N2a) cells transiently expressing mutated PrP were exposed to brain homogenates prepared from mice infected with the RML, Me7 or 301V prion strains. In each case, mutated PrP was converted into PrPSc as judged by Western blotting. These findings raise the possibility that the N2a cell line can support replication of different strains of prions.

-

-

-

-

Strain-specific propagation of PrPSc properties into baculovirus-expressed hamster PrPC

More LessThe conversion of the cellular isoform of the prion protein (PrPC) to the abnormal disease-associated isoform (PrPSc) has been simulated in cell-free conversion reactions in which PrPSc-enriched preparations induce the conformational transition of PrPC into protease-resistant PrP (PrP-res). We explored the utility of recombinant hamster (Ha)PrPC purified from baculovirus-infected insect cells (bacHaPrPC) as a replacement for mammalian-derived HaPrPC in the conversion reactions. Protease-resistant recombinant HaPrP was generated after incubation of 35S-bacHaPrPC with PrPSc-enriched preparations. Moreover strain-specific PrP-res was also reproduced using insect-cell derived HaPrPC and PrPSc from two different strains of hamster-adapted transmissible mink encephalopathy, designated hyper (HY) and drowsy (DY). Two strain-mediated properties were tested: (i) molecular mass of the protease-digested products and (ii) relative resistance to proteinase K (PK) digestion. Similar to in vivo generation of PrPHY and PrPDY, the converted products selectively reproduced both characteristics, with the DY conversion product being smaller in size and less resistant to PK digestion than the HY product. These data demonstrate that non-mammalian sources of recombinant HaPrP can be converted into PK-resistant form and that strain-mediated properties can be transmitted into the newly formed PrP-res.

-

Volumes and issues

-

Volume 105 (2024)

-

Volume 104 (2023)

-

Volume 103 (2022)

-

Volume 102 (2021)

-

Volume 101 (2020)

-

Volume 100 (2019)

-

Volume 99 (2018)

-

Volume 98 (2017)

-

Volume 97 (2016)

-

Volume 96 (2015)

-

Volume 95 (2014)

-

Volume 94 (2013)

-

Volume 93 (2012)

-

Volume 92 (2011)

-

Volume 91 (2010)

-

Volume 90 (2009)

-

Volume 89 (2008)

-

Volume 88 (2007)

-

Volume 87 (2006)

-

Volume 86 (2005)

-

Volume 85 (2004)

-

Volume 84 (2003)

-

Volume 83 (2002)

-

Volume 82 (2001)

-

Volume 81 (2000)

-

Volume 80 (1999)

-

Volume 79 (1998)

-

Volume 78 (1997)

-

Volume 77 (1996)

-

Volume 76 (1995)

-

Volume 75 (1994)

-

Volume 74 (1993)

-

Volume 73 (1992)

-

Volume 72 (1991)

-

Volume 71 (1990)

-

Volume 70 (1989)

-

Volume 69 (1988)

-

Volume 68 (1987)

-

Volume 67 (1986)

-

Volume 66 (1985)

-

Volume 65 (1984)

-

Volume 64 (1983)

-

Volume 63 (1982)

-

Volume 62 (1982)

-

Volume 61 (1982)

-

Volume 60 (1982)

-

Volume 59 (1982)

-

Volume 58 (1982)

-

Volume 57 (1981)

-

Volume 56 (1981)

-

Volume 55 (1981)

-

Volume 54 (1981)

-

Volume 53 (1981)

-

Volume 52 (1981)

-

Volume 51 (1980)

-

Volume 50 (1980)

-

Volume 49 (1980)

-

Volume 48 (1980)

-

Volume 47 (1980)

-

Volume 46 (1980)

-

Volume 45 (1979)

-

Volume 44 (1979)

-

Volume 43 (1979)

-

Volume 42 (1979)

-

Volume 41 (1978)

-

Volume 40 (1978)

-

Volume 39 (1978)

-

Volume 38 (1978)

-

Volume 37 (1977)

-

Volume 36 (1977)

-

Volume 35 (1977)

-

Volume 34 (1977)

-

Volume 33 (1976)

-

Volume 32 (1976)

-

Volume 31 (1976)

-

Volume 30 (1976)

-

Volume 29 (1975)

-

Volume 28 (1975)

-

Volume 27 (1975)

-

Volume 26 (1975)

-

Volume 25 (1974)

-

Volume 24 (1974)

-

Volume 23 (1974)

-

Volume 22 (1974)

-

Volume 21 (1973)

-

Volume 20 (1973)

-

Volume 19 (1973)

-

Volume 18 (1973)

-

Volume 17 (1972)

-

Volume 16 (1972)

-

Volume 15 (1972)

-

Volume 14 (1972)

-

Volume 13 (1971)

-

Volume 12 (1971)

-

Volume 11 (1971)

-

Volume 10 (1971)

-

Volume 9 (1970)

-

Volume 8 (1970)

-

Volume 7 (1970)

-

Volume 6 (1970)

-

Volume 5 (1969)

-

Volume 4 (1969)

-

Volume 3 (1968)

-

Volume 2 (1968)

-

Volume 1 (1967)

Most Read This Month